Cette (in)capacité à dire non revient fréquemment et a des impacts sur les relations à soi et aux autres, avec par exemple des manifestations sur le développement de carrière, l’équilibre vie privée vie professionnelle.

Team & Leader Performance via Harmonized Relationship

Confinement. Couvre-feu. Incertitudes. Pandémie. Conflits armés.

Que vous les perceviez comme des éléphants dans la pièce ou comme des gaz invisibles et pourtant bien présents, ces éléments ont un impact. Impact individuel, impact collectif.

Au regard de mes conversations de coaching, je constate que cet impact comporte un point commun : nous faire réagir, de manière instinctive. Chacun à notre manière. Cette réaction, naturel élan de survie, n’est pourtant pas la plus efficace, ni la plus adaptative, dans des situations complexes.

Alors comment nous (re)mettre en mouvement ? Sortir de cette ornière où la pandémie nous pousse insidieusement ? Comment nous (re)connecter à notre créativité, afin de trouver des stratégies d’adaptation face à tous ces éléments que nous vivons, afin de vivre sans subir ? Afin de vivre plutôt que de sur-vivre ?

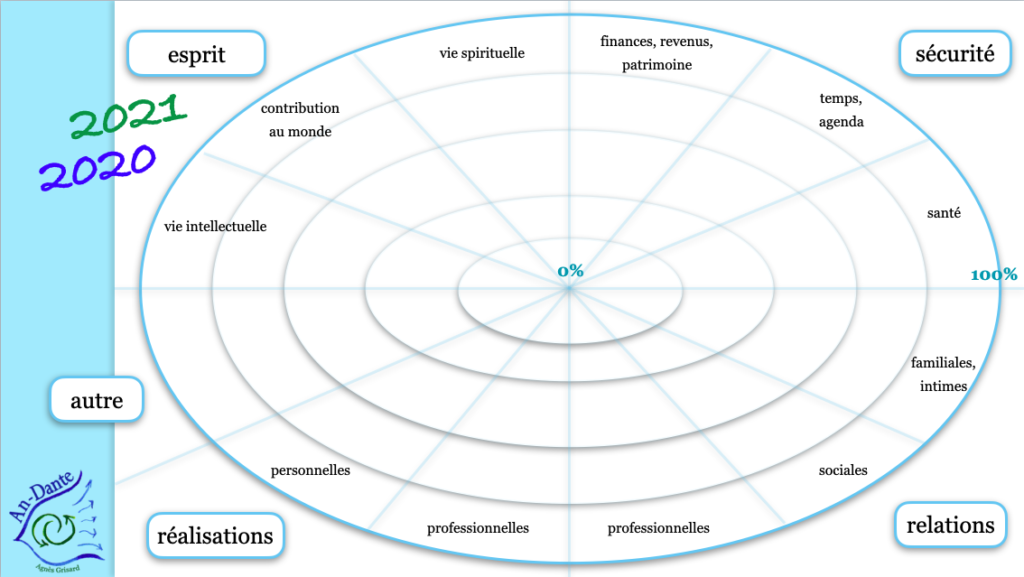

En ce début de nouvelle année, au démarrage d’un nouveau cycle, je vous propose un exercice pour imaginer votre prochain voyage.

On the eve of this year, at the beginning of a new cycle, here is an exercise to imagine your next journey.

article in English below

Les « boutons rouges » sont les intolérances qui nous déclenchent émotionnellement, à chaque fois que quelqu’un appuie dessus ou une situation nous y confronte.

Ces réactivités sont à l’origine de bien des conflits dans les équipes.

The « red buttons » are the intolerances that trigger us emotionally, every time someone presses them or a situation confronts us.

These reactivities are at the root of many conflicts in teams.

Leur effet est de nous faire sur-réagir à la situation, ce dont nous sommes peu conscients au moment où cela est déclenché, et que nous pouvons observer par analyse réflexive, après coup. Leur déclenchement nous fait basculer en mode instinctif, où nous réagissons en défense, sur un mode très automatique et rarement adapté à la situation.

Par exemple, une équipe en conflit, découvre lors d’un coaching que le conflit est alimenté par des intolérances individuelles : ne pas être reconnu·e comme à la hauteur, recevoir des ordres, rendre un rapport incomplet ou imparfait, être impuissant·e à calmer deux collègues…

Pour développer notre Leadership Complexe, il est utile de les connaitre, et d’apprendre à les gérer, d’abord pour soi, puis dans la relation.

Their effect is to make us overreact to the situation, which we are little aware of at the time it is triggered, and which we can observe by reflexive analysis, after the fact. Their triggering makes us switch to instinctive mode, where we react in defense, in a very automatic mode and rarely adapted to the situation.

For example, a team in conflict, discovers during a coaching that the conflict is fueled by individual intolerances: not being recognized as up to the task, receiving orders, making a report incomplete or imperfect, being powerless to calm two colleagues…

To develop our Complex Leadership, it is useful to know them, and to learn to manage them, first for oneself, then in the relationship.

Article in English below

Dans ce article, nous vous proposons une plongée dans le monde des émotions, pour mieux les comprendre, et mieux les apprivoiser !

In this article, we invite you to dive into the world of emotions to better understand and embrace them!

« Le stress n’est pas une émotion mais bien l’effet d’une compression que les exigences extérieures imposent à nos émotions. Ce qu’il faut ce n’est donc pas éliminer le stress : c’est être en contact avec nos émotions et nous servir de l’information qu’elles contiennent pour agir sur le stress en tenant compte de nos besoins. » Michèle Larivey.

“Stress is not an emotion but rather the effect of pressure that external demands impose on our emotions. The goal is not to eliminate stress but to stay in touch with our emotions and use the information they provide to address stress while considering our needs.” — Michèle Larivey.

En d’autres mots, le stress nous donne une information que quelque chose « bug » dans notre cerveau ! Ou du moins dans notre façon de percevoir la situation. Cette information est constituée notamment de nos ressentis et émotions. A nous d’en faire quelque chose pour changer la situation et nous transformer. Dans l’instant. Et c’est aussi un travail qui porte sur le long terme.

En voici des clefs concrètes.

Nos apprentissages sur la vie émotionnelle, nous viennent de notre famille et notre culture. Ca, c’est fait !

Cela dit, bonne nouvelle : nous pouvons poursuivre nos apprentissages toute notre vie !

Sentiment : sans sensation corporelle forte, durable, délicat et subtile

Émotion : avec sensation corporelle plus ou moins intense, non durable, envahissante, réaction intérieure vive avec une intensité

Expérience émotive : résultat du processus d’experiencing, faite d’émotions, des sensations qui en découlent, des pensées. Se centrer, c’est porter son attention sur l’expérience immédiate pour l’accueillir et y accéder.

Les émotions ou les sensations sont un signal de ce que nous vivons. En qualité et en intensité. Ce signal a une signification subjective, lié à notre système de pensée individuel, et elle renvoie à un besoin, dans l’instant présent.

Les sensations nous parviennent par nos cinq sens vue, ouïe, toucher, odorat, goût, et le mouvement.

Les émotions sont au cœur de notre système de communication. Les émotions sont décrites par les mots que nous leur affectons et les sensations qui leur sont liées. Par exemple, si j’ai peur, je relie ce mot à la sensation d’avoir le coeur qui accélère, le souffle court, la voix chevrotante et peut-être aussi une salivation différente (en plus ou en moins)

Plus nous sommes capables d’exprimer et d’extérioriser nos émotions, plus le contact avec nous est enrichissant pour ceux qui nous côtoient. Nous leur donnons ainsi accès à notre vie intérieure. Et ce que nous vivons les concerne souvent.

Michèle Larivey scinde les émotions en 4 catégories (que l’on retrouve également peu ou prou chez d’autres auteurs) :

Chacune des émotions simples rend compte d’un besoin. Elle est donc la clef d’accès au besoin et la satisfaction de celui-ci éteint l’émotion qui n’a alors plus besoin de se manifester puisque le besoin est comblé.

Certaines émotions se manifestent par rapport au responsable ou à l’obstacle, telles que l’amour, l’affection, la fierté. Le besoin peut alors être plus enfoui.

Les émotions d’anticipation concernent ce qui pourrait survenir. Elle sont le fruit de notre imagination, telles que l’excitation, l’appétit, l’inquiétude, la peur, le trac. Elles sont aussi des indicateurs de nos besoins sous-jacents.

Quand un besoin est satisfait, le système est à l’équilibre. Quand il n’est pas satisfait ou qu’un nouveau besoin apparaît, le système est en déséquilibre. Chez l’humain, le besoin est physique -exemple la soif : besoin d’eau- et psychologique -et peur : besoin de protection-.

L’émotion nous signale donc à quel point nos besoins sont satisfaits ou non.

Et chacun.e est responsable de la satisfaction de ses propres besoins.

Le travail sur les émotions consiste à faire des allers-retours entre le ressenti d’une sensation corporelle, et des mots précis pour nommer l’émotion. Cela nous permet d’accéder à la compréhension de ce que nous vivons.

Cette expérience de boucle du processus émotionnel s’enrichit au fur et à mesure de la pratique. Et cet entrainement augmente notre intelligence émotionnelle.

Le processus naturel de croissance, ou processus vital d’adaptation, se déroule en 5 phases :

Ci-après, vous trouverez, par émotion, les caractéristiques de l’émotion, du sentiment ou d’un autre signal, et l’intérêt de ce signal. Ce sont des pistes pour clarifier ce que vous pourriez faire de ces signaux.

Nos émotions sont des signaux de notre intelligence et des manifestations que nous sommes vivants et en mouvement.

Alors et si nous apprenions à les entendre et à nous servir d’elles comme levier de développement dans la relation à nous-même et aux autres ?

In other words, stress gives us information that something is “glitching” in our brain—or at least in how we perceive a situation. This information consists of our feelings and emotions. It’s up to us to do something with it—to change the situation and transform ourselves, both in the moment and in the long term.

Here are some practical keys to understanding and managing stress.

Our emotional learning comes from our family and culture. That part is already set. But the good news is that we can continue learning throughout our entire lives!

Feeling : does not involve strong bodily sensations, subtle, delicate, and long-lasting.

Emotion : involves bodily sensations of varying intensity, temporary, can be overwhelming, intense inner reaction.

Emotional Experience

It is the result of an internal process that includes emotions, the sensations they produce, and our thoughts. Focusing on emotions means paying attention to the immediate experience, accepting it, and accessing its deeper meaning.

Emotions and sensations signal what we are experiencing—both in quality and intensity. These signals are subjective and tied to our personal thought systems. They point to an unmet need in the present moment. Our sensations come through our five senses (sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste) and movement. Emotions are at the core of human communication. They are expressed through both words and the physical sensations they trigger.

For example, if I feel afraid, I might notice my heart racing, shortness of breath, a shaky voice, changes in saliva production.

The more we can express and externalize our emotions, the more meaningful our interactions become. Sharing our inner world allows others to understand us—and often, what we feel affects them too.

Psychologist Michèle Larivey classifies emotions into four categories (a system echoed by other experts as well):

Positive simple emotions indicate satisfaction and are linked to the instinctive calm response described in neuroscience.

• Pleasure

• Joy

• Delight

• Affection

• Pride

• Love

Negative simple emotions indicate dissatisfaction and are linked to the neurosciences instinctive governance fight-or-freeze.

• Boredom

• Sadness

• Disappointment

• Melancholy

• Disgust

• Pain

• Anger

• Rage

• Impatience

• Frustration

Each simple emotion is connected to a need. Once the need is met, the emotion naturally fades. Some emotions relate specifically to a person or obstacle, such as love, affection, or pride. These emotions may point to deeper, hidden needs.

These are emotions about what might happen. They come from our imagination and help reveal underlying needs, like excitement, appetite, anxiety, fear, stage fright. They are also signs of unsatisfied needs.

Mixed emotions mask deeper issues and require careful analysis.

• Guilt

• Jealousy

• Contempt

• Pity

• Disgust

• Shame

Counter-Emotions

These are physically intense emotions that reveal what we suppress or try to avoid. They are linked to the flight instinctive governance.

• Anxiety

• Panic

• Nervousness

Pseudo-Emotions

• Feeling rejected

• Being conflicted about someone you love, feeling trapped, insignificant, or amazing

• Feeling confused, depressed, or emotionally drained

• Behaviors : openness, curiosity, warmness, hostile, judgments (which are not feelt) like stupid, ridiculous, pathetic

When a need is met, we feel balanced. When it isn’t met, or when a new need arises, we feel off balance. Human needs are both physical (e.g., thirst → need for water), psychological (e.g., fear → need for protection)

Our emotions tell us how well our needs are being met.

And importantly: each person is responsible for meeting their own needs.

The key to managing emotions is going back and forth between bodily sensations and specific words to name the emotion.

This process helps us understand what we’re experiencing and improves with practice—strengthening emotional intelligence over time.

1. Emergence – The emotion appears. At first vague, it becomes clearer when we stay present with it. Naming the emotion completes this phase.

2. Immersion – Fully experiencing the emotion without resistance. Many people struggle here, but accepting an emotion as it is allows progress.

3. Development – Understanding its nuances and complexities.

4. Insight – Gaining clarity about why the emotion is there. True insight is a sudden realization, unlike premature explanations that may arise earlier.

5. Unifying Action – Expressing or acting on the insight in a way that aligns with your values. This resolves the emotional cycle and makes space for new experiences.

Each emotion carries valuable information:

Tenderness & Tears

Fulfills an emotional need.

Anger

A sign of imbalance.

Manifests dissatisfaction, a lack, or an unmet need.

Contentment

Satisfaction.

Feel it, surrender to the emotion, and nourish yourself with it.

Desire

An emotion of anticipation, fantasy.

Provides information about a need, an aspiration, a search for balance and satisfaction; a sign of vitality.

Boredom

Lack of meaning.

An unmet need, frustration, passivity; helps identify what truly matters, break free from “shoulds,” reconnect with oneself, and take ownership of one’s choices.

Impatience

Doing something insignificant while neglecting what truly matters.

Indicates that we are wasting time and invites us to invest it in something more meaningful.

Fear

A subjective anticipation of danger.

Encourages us to assess the reality of the danger and take measures to protect ourselves.

Pleasure

Satisfaction of a need, the harmonious fulfillment of a vital requirement.

Indicates that a need has been met.

Sadness

Signals an emotional loss.

Invites us to identify and address this lack, restoring our psychological energy.

Love

A spontaneous emotional movement toward someone who brings us satisfaction and inspires us to surpass ourselves.

Reveals the presence of crucial needs or aspirations, the desire to be recognized for our capacity to attract, and the need for essential validation from the other person.

Healthy Guilt

A deliberate action against my values.

Highlights an internal imbalance or self-disagreement; once clarified, it allows us to take responsibility and make amends.

Guilt of Concealment

Making one’s actions seem more acceptable to oneself and others.

Encourages us to take responsibility for our actions.

Disgust

Weariness, aversion, and disapproval.

Indicates an overload, that we have gone too far.

Pride

A form of self-satisfaction infused with self-esteem.

Indicates that we have taken action up to our standards and invested ourselves in it; may be perceived by others as arrogance or boasting, which invites us to own our achievements and express this emotion openly.

Shame

Social guilt triggered by others’ judgment.

Encourages us to recognize what we struggle to accept about ourselves, clarifies how we judge ourselves, and highlights the importance we place on others’ opinions. Offers an opportunity for personal growth and behavioral freedom.

Jealousy

Anger toward someone who has something I desire.

Through the envy it carries, invites us to identify our own needs and acknowledge our resistance to fulfilling them.

Romantic Jealousy

A mix of fear and anger triggered by insecurity.

Reflects the fear of losing an important benefit from the relationship and insecurity about our attractiveness. Encourages self-confidence development and relationship clarity.

Contempt

• Concealed Contempt: Anger and fear, possibly jealousy, dissatisfaction, a defense against hurt, rejection of the relationship.

• Reactive Contempt: Anger, an admission of disagreement with someone who does not meet our moral expectations, a desire for connection.

Encourages self-exploration to uncover the true cause behind our contempt, leading to acceptance of our vulnerability and honest emotional expression.

Pity

Underlying contempt.

Masks an emotion under socially acceptable appearances, requiring deeper identification.

Fatigue

Excessive emotional expenditure.

A large investment of psychic energy to suppress emotions or fatigue following an intense emotional experience. Signals a need for emotional and physical rest. Encourages opening up to the underlying emotion by breathing and embracing it.

Embarrassment

Occurs when we deny ourselves pleasure or contentment and attempt to replace it with indifference.

Indicates inner conflict between pleasure and its repression due to an inability to fully embrace it or the vulnerability it exposes. Disappears when we accept and openly experience pleasure.

Blushing, Memory Loss, Loss of Focus, Stuttering

An internal struggle between an emerging emotion and the desire to hide it.

Encourages us to accept both the emotion and its expression, embracing ourselves as we are by identifying the emotion seeking to surface and its triggers.

Disappointment

Indicates that an expectation was not met.

Encourages us to clarify our initial expectations and desires, then examine our role and others’ roles in fulfilling them.

Distancing, Withdrawal

Reflects dissatisfaction, frustration, or even anger that remains unexpressed.

Encourages us to express what we feel and embrace the liveliness of the relationship.

Frustration

A state of dissatisfaction, coupled with a sense of injustice, generating anger, jealousy, or sadness.

Encourages us to take an active role in relationships, take charge of our lives, and ensure our needs are met.

Helplessness

Inability or impossibility to take action or achieve goals.

Highlights obstacles preventing satisfaction, urging us to distinguish between what is within our control and what is not. This clarification helps break free from paralysis.

Manipulation

An action imposed on us, pushing us to do things we do not want to do, triggering emotions we resist, making us vulnerable to control.

Encourages awareness of the emotion at play and resistance to manipulation.

Gratitude

A sense of indebtedness to someone who has done us a favor.

Indicates that we have received something valuable, perceived as a privilege. To fully embrace the experience, we must express our gratitude, which fosters a sense of fulfillment and strengthens the relationship.

Our emotions are not obstacles—they are signals. They guide us toward self-awareness and growth.

So, what if we learned to listen to them and use them as tools for personal development and deeper connections?

Nous prenons plusieurs milliers de décisions par jour, un grand nombre d’entre elles de manière automatique et inconsciente ou peu consciente. Comme mettre des lunettes, marcher, respirer…

Que se passe-t-il dans notre cerveau dans le processus de prise de décision ?

Comment se passent nos prises de décision ?

Qu’est-ce qui fait que nos émotions influent sur nos décisions ?

Comment notre capacité de réflexion influe-t-elle ?

Parfois, nous sommes « déclenchés » par des situations. Ce qui entraine une réactivité émotionnelle instantanée, dont l’intensité peut nous paraitre étonnante ou inappropriée, avec du recul.

Que se passe-t-il dans ces situations d’hyper-réactivité émotionnelle ?

Sometimes we are « triggered » by situations. This leads to an instant emotional reactivity, the intensity of which may seem surprising or inappropriate, with hindsight.

What happens in these situations of emotional hyper-reactivity?

Quelque chose nous « déclenche », mettant immédiatement en route notre gouvernance instinctive, celle qui est chargée de notre survie. Autant dire que la réponse ne traine pas !

Ensuite, les choses se déroulent, selon 3 types de scénarios illustrés ci-dessus :

Scénario 1 : nous ne faisons rien de particulier, et les choses évoluent dans le temps.

Scénario 2 : nous activons une bascule mentale, et le signal de stress diminue progressivement

Scénario 3 : nous nous rendons compte qu’il se passe quelque chose, avant d’arriver tout en haut de l’échelle du stress et nous activons une bascule mentale.

L’impact du stress, notamment en terme de consommation d’énergie est proportionnel à la surface sous la courbe de chaque scénario. Il est donc plus écologique pour nous d’être dans le scénario 3 !

Bonne nouvelle, basculer mentalement s’apprend et se travaille par de l’entrainement quotidien.

Etape 1 : se rendre compte que nous avons commencé l’ascension de l’échelle, que nous avons quitté notre état de calme

Etape 2 : identifier ce qui nous déclenche, en nous interrogeant : quelle valeur est touchée ?, sur quel « bouton rouge » a-t-on appuyé ?, quel besoin n’est pas satisfait ?

Etape 3 : déclencher un exercice de bascule mentale pour revenir à notre calme, prendre de la hauteur

Etape 4 : apprendre de la situation, et s’entrainer, pour être de plus en plus capable de passer du scénario 1, au scénario 2, puis au scénario 3.

Pour aller plus loin : Echelle d’inférence

Something « triggers » us, immediately setting in motion our instinctive governance, the one that is responsible for our survival. In other words, the answer does not drag!

Then, things unfold, according to 3 types of scenarios illustrated above:

Scenario 1 : we do not do anything in particular, and things evolve over time.

Scenario 2: we activate a mental switch, and the stress signal gradually decreases

Scenario 3: we realize that something is happening, before we arrive at the very top of the stress ladder and we activate a mental switch.

The impact of stress, particularly in terms of energy consumption, is proportional to the area under the curve of each scenario. It is therefore more ecological for us to be in scenario 3!

Good news, switching mentally is learned and worked on through daily training.

Step 1 : realize that we have started the climb of the ladder, that we have left our state of calm

Step 2 : identify what triggers us, asking ourselves: what value is affected?, on which « red button » was pressed?, what need is not satisfied?

Step 3: trigger a mental rocking exercise to return to our calm, gain height

Step 4 : learn from the situation, and train, to be more and more able to move from scenario 1, to scenario 2, then to scenario 3.

To go further: Inference scale

in English below

Il reste une part de votre gâteau préféré au milieu de la table. Le hic, c’est que chacun des gourmands autour de la table voudrait bien s’en délecter…

Comment réagissez-vous ?

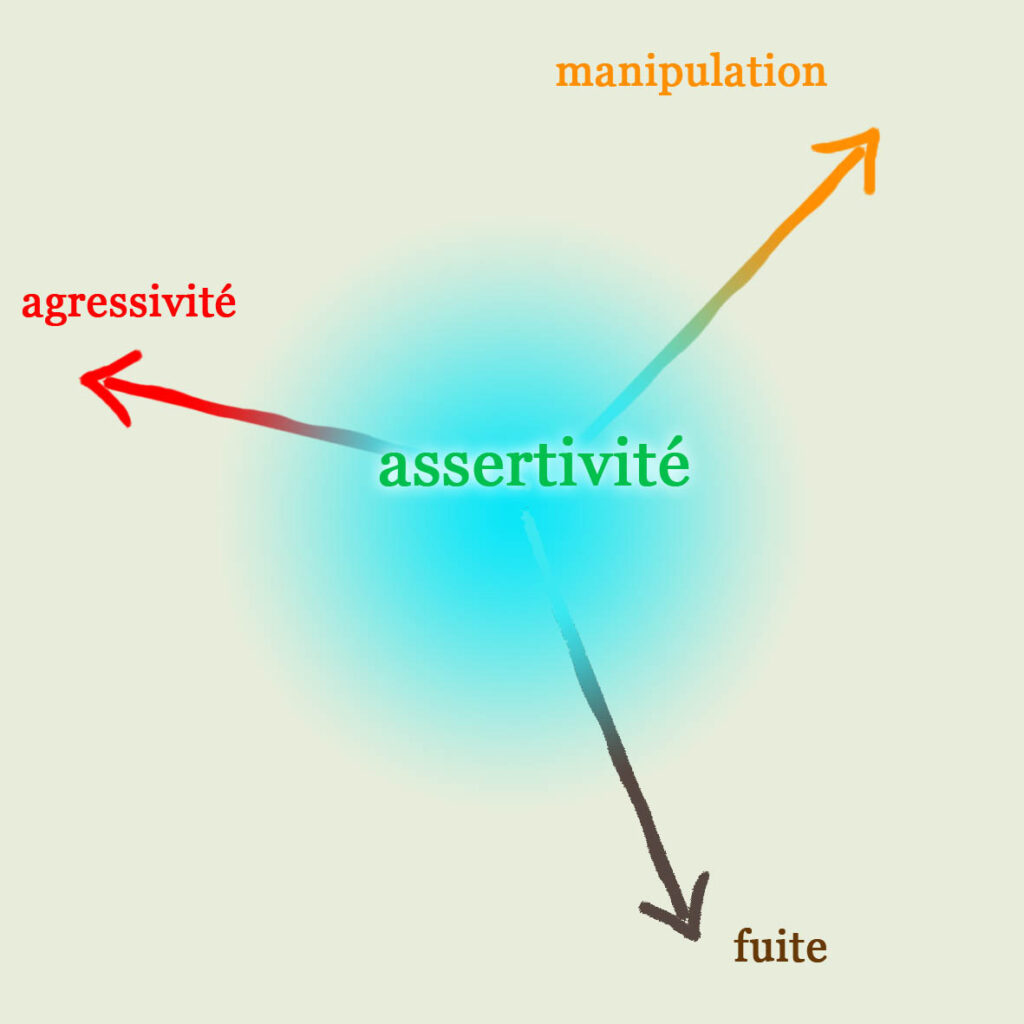

L’assertivité peut vous aider à vivre au mieux ce type de situation 😉 et bien d’autres !

There’s one slice of your favorite cake left in the middle of the table. The catch? Everyone at the table has their eye on it…

How do you react?Assertiveness can help you navigate this kind of situation—and many others—smoothly!

L’assertivité c’est la posture dans laquelle vous n’êtes :

Vous êtes donc au centre du schéma.

Dans l’exemple :

Dans toutes les relations humaines, les échanges sont liés à la posture de la personne. Celle-ci est très liée à l’éducation et au mode de fonctionnement familial. Et bien sûr à la situation et aux interlocuteurs en présence ! Enfin, votre niveau de stressabilité rentre aussi en ligne de compte, c’est à dire la position du curseur sur une échelle stressé-calme.

En prendre conscience vous permet de faire évoluer votre posture, petit à petit, sur des sujets peu importants au départ, puis sur des sujets plus cruciaux pour vous !

Pour être assertive-assertif, il faut que vous soyez connecté/e à vos besoins. Pour cela, je vous invite à lire l’article Comment utiliser la pyramide de Maslow, pour soi et son équipe ? Et si vous faisiez un tour du côté de vos besoins, pour mieux communiquer ?

Enfin, culturellement, les femmes sont le plus souvent incitées à prendre soin des autres, donc à faire passer leurs besoins après ceux de leur entourage ! Je fais allusion au mythe de l’épouse modèle et de la mère nourricière ou mère parfaite, qui se traduit en entreprise par celui de l’employée modèle et fidèle…

Lorsque vous exprimez votre posture de façon assertive, utilisez des tournures de phrases comme :

Et vous, quels début de phrases utilisez-vous pour être assertive/assertif ?

Assertiveness is the stance in which you are:

1. Neither aggressive,

2. Nor avoidant,

3. Nor manipulative.

You are therefore at the center of the spectrum.

In the example:

• An avoidant reaction would be to say nothing and let others share the last piece of cake.

• An aggressive reaction would be to devour it before anyone else has a chance to react.

• A manipulative reaction would be to tell the others that they already had a bigger piece than you and that it really wouldn’t be fair if they took more, or to guilt-trip them about their figure…

• An assertive reaction would be to simply say that you really want that piece.

In all human interactions, communication is influenced by a person’s stance. This is closely linked to upbringing and family dynamics, as well as the specific situation and the people involved. Additionally, your stress tolerance plays a role—meaning where you fall on the stressed-to-calm spectrum.

Becoming aware of this allows you to gradually adjust your stance—first in less significant situations, then in those that matter more to you.

To be assertive, you need to be connected to your own needs. To explore this further, I invite you to read the article How to Use Maslow’s Pyramid for yourself or your team. Maybe It’s Time to Check In on Your Needs for Compassionate communication.

Culturally, women are often encouraged to prioritize others’ needs over their own. This ties into the myth of the “perfect wife” and the “nurturing mother,” which extends into the workplace as the expectation of the “loyal, model employee.”

When expressing yourself assertively, use phrases like:

• It’s important to me to…

• I need to…

• I would like to…

• I wish to…

What about you ? What sentence starters do you use to express yourself assertively?